After much deliberation, we're so excited to announce the shortlists of nominees for the 2024 Rando Awards!

he lies for money

In 2021, I finished writing what I think is the best novel of my career (a massive military wlw fantasy called A Flesh Most Holy And Incandescent). I’m also in the editing stages with a horror novella cowritten with Rich Larson, I’m halfway through a pulpy fantasy novel that’s basically Final Fantasy 7 meets Mad Max meets Vandermeer’s Annihilation, and I have all the foundations in place for what will eventually be my magnum opus - a cosmic-body-horror retelling of the entire French Revolution.

W&W is a fantasy adventure audiobook. It's a full-length novel about a thief who breaks into an ancient temple in search of loot and is soon entangled in a plot to raise an ancient, evil god. It's got goblins and golems, evil warlocks and mechanical beasts, traps and crumbling ledges and death-defying leaps. All the fun stuff from a classic dungeon crawl, or a 70's pulp fantasy paperback.

And it's ALSO a high intensity interval training (HIIT) fitness program where you're the hero.

The Ragged Blade

In stores from June 4th 2019

June 4th, team.

I’m still trying to get my head around that date. June 4th. Three weeks from now.

It’s been a long road we’ve taken, me and this little book. Twelve years since the first words hit the page. Five years of rewrites on what was then called Century of Sand. Two years of queries. Then Parvus Press gave me a chance and we dove back into rewrites for another 18 months, so extensive that the beautiful beast about to hit stores all across the US is something entirely new, all sleek and honed and ready for action.

I’m so proud of what me and my editor Kaelyn have created. It’s a bloody good book, and I can’t wait for you all to see it.

Three weeks. That’s all.

Now, here comes the sales pitch.

If you want to grab a copy of The Ragged Blade – and I sincerely hope you do – then the best thing you can do is preorder. Why?

You get the book as soon as possible

You do all sorts of magical algorithmic things that makes The Ragged Blade really visible on Amazon on launch day

You prove to my publishers that there’s a market for books 2 and 3

So grab your copy of The Ragged Blade today! You can do that direct from the publisher, or through:

Amazon Kindle

Amazon Paperback

B&N Nook and Paperback

Indiebound

or use Bookto to grab The Ragged Blade from a local Aussie bookshop!

Thanks, team. You’re all stars.

Back in 2010-2014 I was writing a lot. 3 novels a year, 3-4 drafts each, plus time for side projects like X-Com fanfic (I promise to revive the B-Team one day!), all while working as a design contractor and teaching part-time.

I felt like I’d cracked the code to productivity. That the energy would never fizzle out.

Then, in 2014, I went back to school to get my Masters of Teaching. In 2016, I began teaching high school.

Surprise! I fizzled.

This is partly because teaching consumes your entire life (80 hour work weeks, every week, forever.) But what I also found was that, even when I did have the time, I couldn’t make the words come. What’d once been so easy was now a struggle. I’d sit down with three hours to spare and end up with 200 limp words and a Youtube playlist of AGDQ speedruns.

Writing wasn’t an escape any more. It was extra work, and it was somehow harder than the real work.

From 2015-2018, I wrote one book (Rust Four), edited two others (The Ragged Blade, which I’m immensely proud of, and God Factory, which is getting better), and abandoned a lot of half-finished drafts along the way. At the end of 2018, I looked back at my output and decided this was officially Not Good Enough.

So, over Christmas, I decided to take a serious look at my work habits, figure out what was holding me back, and reboot.

It worked.

For the past weeks I’ve been writing non-stop. Projects are moving fast. And I’m not smashing out junk words, either. This is good stuff, some of my best, and I can’t wait to show it to you.

Here’s what I changed. I hope it’ll help you too.

Take a look at all the places you write. Living room? Bedroom? Home office? Local cafe? On the train?

Now, in which of these places are you most productive?

For me, it’s a) the home office and b) on the train. Why? In my office, I’m at a desktop. I sit upright, professional. No distractions in line of sight, and my wife works in the same room as me so she’ll call me out if I get distracted by cat vids. As for the train, there’s no internet to pull me off-task.

Now, where was I doing most of my writing over the past four years?

In the living room, on my laptop. Slumped on the couch, TV in the background. Why? Because my laptop charger was in the living room. Because there was more space there for snacks. Because it was comfortable and nobody would poke me if I got off-task.

Shockingly, I didn’t get much writing done.

Your environment contributes to your productivity and you have to be honest about where you get your best work done. Are you avoiding that spot? Why? Because it’s less comfortable? Because it doesn’t enable your bad habits?

Find your most productive writing spot and stick with it.

What do you need around you to complete your best work?

Some people need mood music. Some people need white noise. Others, the scent of a vanilla-infused candle, and silence. You need to figure out what assists your writing, and what’s pulling you off task.

For me, music with lyrics destroys my productivity. Low-key ambient stuff is great. White noise is best of all.

And yet, I spent the last four years working with background noise, like the TV, Spotify or my podcasts (I’m sorry, Night Vale. You bring out the worst in me).

It wrecked my work.

It took time for me to acknowledge that I was using these things to fill the space in my head when words wouldn’t come. Pretty soon, there was no space left.

I’m back to white noise now. Or, on occasion, lyric free ambient tracks on low volume. The words come a lot easier now.

Create a sensory environment that supports your writing.

After twelve novels, I figured I’d conquered my fear of the blank page.

I was wrong.

From 2014-2018, I would sit down at my laptop with no plan in mind. Not for a chapter, not for a scene, not for a conflict.

I figured I’d written so much that the structure of a good story was innate. Spoilers: that’s bullshit. No goal means no direction, and soon you’re flipping desktops, catching up on AGDQ, re-reading the entire Achewood archives (twice…)

But I never experienced that problem while editing The Ragged Blade. Why? Because I had an excellent team behind me who gave me direction. They worked with me to identify problems, structure solutions, and give me deadlines.

Clear plans & pathways. Who would’ve thought it’d lead to quality writing?

I know many of my writing friends hate writing to a strict outline. I’m not asking for anything strict. No battle plan survives contact with the enemy, after all. But walking into battle with no plan at all is suicide.

So I forced myself to switch up my routine. Now I always spend the first half hour of the day creating a handful of notes that will guide my writing. They aren’t extensive. Maybe a single scene, maybe a few linked scenes, maybe a single line of dialogue that sparks a conflict. But I never, ever, sit down at my computer without a plan.

Take a little time to plan your work and you’ll banish the paralysis of uncertainty.

A couple years back I wrote an article called Why 1000 Words a Day is Easy and Quick. The gist: 100 words is a small, achievable goal. 1000 words is 100×10. Do ten small things a day, and you hit your target. Do that every day for a year and you have 365,000 words.

Some time between 2013 and now, I forgot that lesson.

I used to do 3000 words on a bad day, 6000 words on a good one. So I stopped thinking about small goals. I’d wake up and say, cool, let’s do 1000 words before breakfast. 3k before lunch. Add another 1k after dinner.

But once my job started taking up more of my day (and evening, and night, and weekends…) I couldn’t find the time to write 1000 words. And I’d lost the habit of setting small, measurable, achievable goals.

Most days I didn’t write anything.

So I went back to basics. I don’t write 1000 words at a time any more. I do 100 (200 if I’m feeling feisty) and then stop, and congratulate myself, and do it again. I measure myself against the clock – can I do 100 words before 1pm? Okay, cool, that wasn’t too hard. Can I do it again? Not quite, but it’s a start. How about another 100 by 1:15?

And so on, and so on.

By focusing on small tasks, I’ve found myself reaching my daily wordcounts faster and with less stress. And I find I can fit these little tasks into small time slots. Five minutes before I have to leave for work? If I have a plan, I can do 100 words. Ten minutes at the end of a lunch break? Lock the door, close Chrome, open the planning doc, write 200 words.

Forget hitting 1k, 2k, 3k. Just do the paragraph. Set yourself a strict time limit. Get it done. Repeat.

Little, simple goals quickly turn into big achievements.

Intrinsic motivation: something internal that drives you to succeed. For example, writing a book because it makes you happy. Bashing out a draft because it improves your overall craft. Writing as personal therapy, and so on.

Extrinsic motivation: an external reward pushing you forward. Example: writing a book because you’re on a deadline, bashing out a draft because you’ll celebrate completion with a cake, and so on.

I believe the best (or at least, the most productive) authors have a mixture of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. They want to improve their craft. They find satisfaction in good storytelling. But they’re also rewarding themselves along the way, either with chocolate, relaxation time, five minutes on Facebook, hard cash, etc, etc.

I write because I love writing. But I don’t always love writing. Some days it’s a trial. Some days I want to burn my manuscripts and go back to flipping burgers. And throughout 2014-2018, my intrinsic motivation fell through the floor.

That’s where extrinsic motivation comes in.

I got myself back in the writing seat by rewarding myself every time I hit a small milestone. What’s a good reward? That’s up to you, but I recommend the thing you wish you were doing instead of writing. If there’s nothing you’d rather do than write, then congrats! You don’t need any extrinsic motivation that day. But that feeling won’t, can’t, last forever.

My rewards: five mins of social media. Playing a single round on a mobile game. I get to do that every 200 or so words. Every 1000 words, I get something bigger. Lunch. A cup of coffee. A ten min slice of Pet Collective.

What’s absolutely necessary is that you don’t cheat. Extrinsic motivation doesn’t exist if you can break the rules and grab a cup of coffee any time you want. You have to work for it, or the pressure to write vanishes.

Extrinsic rewards shouldn’t overtake intrinsic rewards. I don’t mind treating writing as a job, but if you’re writing 100% for the next treat (whether that’s a snack or a paycheque), then writing becomes a bad job. But a balance between the two? That’s the sweet spot.

And the greatest extrinsic motivator of all time? The need to pee. Deny yourself the toilet until you hit a small wordcount goal and damn, you will hit that goal fast. (note – a SMALL wordcount, like, “I can’t go to the bathroom until I hit the next 100 word milestone.” Not “I can’t use the bathroom until I smash out this 3000 word chapter.” Be sensible. Don’t damage your body in pursuit of big wordcounts.)

By going back to small goals, rewarding myself regularly, and depriving myself of necessary things until I hit certain milestones, I pushed my writing output through the roof.

Use small rewards to keep yourself pushing to the next goal, but be strict and never break your own rules.

Get yourself in the right place to write. Somewhere without distractions, where you feel you can devote the necessary attention to your work.

Turn off the music, or at least find music that won’t interfere with your prose.

Start each writing session with a small plan that will banish the paralysis of the blank page.

Set small, achievable goals with strict time limits. Repeat them over and over.

Motivate yourself with small rewards, like a blast of social media, a snack, or a trip to the bathroom.

The result? I’ve gone from writing 1000 words in an average week to 3000 words a day. Century of Sand 2 is flying. The God Factory edits are going great. An as-yet unnamed fantasy novella is half-done.

I’ve got my groove back. If you’ve lost yours, I hope this helps you find it.

If this post was helpful, then I have a favour to ask. Can you share it around? I’d love to help more people, and have more folk discover me in the process.

If you really, really want to do me a solid, try one of my books! I do horror, scifi, fantasy, all sorts of stuff! Not to mention my big fantasy debut, The Ragged Blade, which comes out from Parvus Press in mid 2019 and is now available for paperback preorder…

How many times have I rewritten this sucker now? Too many. But I have a plan for this novel now, and I’m confident I can really make it sing. Just gotta find the time in between revising Century of Sand 2…

It’ll happen. I promise.

—

CEMETERY DOGS

A YOUNG ADULT HEIST CAPERChapter One

—

I kept the pedal to the floor until the sirens had faded into the distance.

My brother William was in the back of the van, trembling, swearing every time we hit a pothole. I watched him in the rear view mirror. Sweat shone on his brow. His hands trembled in his lap. “They’re not gonna catch us, right? Right?”

Dad was sitting beside me, in the passenger seat. He couldn’t sit still. Looking left, looking right, twisting to look back behind us through the window, to see if the cops were closing.

His pupils were huge. I hear adrenaline does that to your eyes. Adrenaline, or fear.

“I think we left them behind,” he said, finally. His voice shook just like William’s hands. On his lap, zip bulging, was a duffel bag. Whenever the van bounced he clutched it tight, like the whole thing would fly away if he didn’t keep it hugged close. “Slow down a little, or you’ll get pulled over for speeding.”

“Yeah!” William called from the back. “Wouldn’t want to lose your learner license!”

My mouth was dry and my heart was smashing against my ribs so hard I thought it’d pop, but my hands were steady on the wheel. I’d been the getaway driver long enough to know how to keep the car moving in a straight line. “What do we do now?”

See, this wasn’t the plan. You have to have a plan if you’re going to rob a bank, and we’d come up with a pretty good one. But not all plans work out.

This job – our last job, we hoped – was one of those times.

A guard at the bank had spooked at the last moment. We’d gotten the cash but barely slipped the police net. The place we’d intended on hiding the car was about fifty miles behind us now, and there were probably twenty cop cars between us and home. Maybe more.

Worse, everything west of San Antonio was flat and bare. Nowhere private to ditch the car and change outfits..

Unless…

“There.” Dad pointed left, off road. “That gully!”

The van almost went airborne a couple times as I pulled off-road, and my knuckles were white by the time we stopped in a gravel pit with tall, sloping walls. Just steep enough to hide us from the road, I guessed.

Dad was already unbuckling his seatbelt. “We have to burn the evidence. Move!”

We’d brought a spare can of gas, enough for a small fire. Dad and William’s orange hi-vis vests became plastic puddles and the paper masks we’d all worn as disguises turned to ash. Our wigs burst into blue flame and the BB gun slumped like a marshmallow, hissing in the heat.

“Clothes too,” Dad said.

William and I looked at each other uncomfortably, but we knew he was right. We took turns, changing in the back of the van and tossing everything we’d worn during the robbery into the fire. My old hoodie, the cap I’d used to hide my long hair, my purple summer top and my jeans turned into one big pile of nylon sludge. The sequins across the butt of those jeans made satisfying popping noises as they melted and turned black.

I don’t know why it felt to good to watch them burn. Old life gone, new life beginning, I guess.

Dad shoveled pebbles and dirt across the whole mess before we left. The sun was setting above the ridges to the west, thin dusk light shining on the buckshot wounds peppered across Dad’s shoulders.

He caught me staring. “Not a word to your mother,” he said. “You know what it’d do to her if she found out.”

I mimed zipping my lips. It helped disguise how sick I felt, looking at his wounds.

Dad nodded. “You’re a good girl, Caecey. Best a father could ask for.”

William and I hid in the back of the van as Dad took the long way back to town, winding south through dusty side-roads before joining Highway 37. Two patrol cars passed us on the way, but their sirens were off and we’d already swapped the plates. Just another boring unmarked van returning to the city after a long day’s work in the country.

At least, that’s what I hoped they’d think.

I tried to stretch out but my heels kept bumping the duffel bag of crinkling, bank-fresh hundreds. Will met my eyes from across the van. Young, bright eyes – he was two years my junior – but right then it felt like I was looking at someone totally new. Someone who’d grown up an awful lot in the past few months.

“That was the last one,” he whispered.

“Yeah.”

“No more banks.”

“That’s what Dad says.”

“Feels weird, doesn’t it?” He nodded at the bag. “It’s like our golden ticket.”

But it didn’t feel like a golden ticket. It felt like I was sitting next to something huge, something ticking. A nuke about to erupt and swallow the van in a blaze of pure white light.

Dad didn’t say a word to us, not until we hit the city outskirts. He dropped us near a bus stop about ten minutes from home. “You two get back safe. Hide the money in the usual place while I dump the van.”

“You sure you’ll be okay?”

Dad grinned, one arm slung over the back of his seat, all cocky like we hadn’t just robbed a bank, hadn’t just been shot at by security, hadn’t just incinerated our disguises and pellet-gun like wannabe Mafiosi. “Why wouldn’t I be okay? We’re set, kids. No more debts. No more being afraid. We pulled it off. All of us, we did it. Together.” He reached out, patted us each on the shoulder in turn. “I’m so proud of you both. This family gets things done. Right?”

“Right,” I said, but there wasn’t any feeling in it. I knew I was supposed to be happy. This was what I’d fought for, after all.

Safety. Success. Dad’s pride.

Even so, something was wrong. A twisting deep in my gut, like a premonition of bad times coming.

Dad drove away, tail-lights vanishing around the corner. The bus was already approaching. William brushed his long dark hair back from his face and slung the bag over his shoulder. “Times are good, Case. Smile, why don’t you?”

But all my attention was on the city below us, pearls of orange streetlights stitching the skyline. Thousands of grunting car horns. The whoop and whine of cop cars.

One and a half million people, and all it’d take was one who’d been in the wrong place at the wrong time. Who could connect Dad to the bank, the bank to the van.

I wanted everything to be perfect. I really did.

But life doesn’t work out that way. Because I’d messed up that day. Messed up real bad.

I just didn’t know it yet.

There’s good news, bad news, and more good news squeezed into this update. Indulge me, friends.

I recently signed a deal with Parvus Press, a relatively new but highly professional US-based publishing house, to revamp and republish the Century of Sand trilogy. I’ll be working with them closely over the next 12-18 months to restructure, edit and polish Century of Sand 1, 2 and 3 into a fresh fantasy epic. Each novel will hit ebook stores in six month increments starting (hopefully) late 2018.

This is awesome news. The Parvus team have been fans of Century of Sand for a while but it was coincidence that brought us back into contact at just the right time to make this deal. Together, we’re going to make the story of Richard, Ana and the Kabbah shine.

As part of this deal, Century of Sand 1 & 2 have been removed from all online retailers. The original editions are gone and won’t return in their new forms for at least a year.

This has also delayed the release of Century of Sand 3 from mid-late 2018 to mid-late 2019. This is so the team at Parvus have time to tear the manuscript apart and put it back together, as well as to give them the space they need to release and promote Century of Sand 1 & 2.

I’m so sorry to all those who’re waiting for Century of Sand 3: The Broken Daughter. I never wanted the time between releases to stretch into George RR Martin levels. What I can say is this: when Century of Sand 3 hits stores, it’s going to be the best possible book it can be, a cracking end to a long and fraught tale of family, forbidden magic and knife-edge survival.

By the time Century of Sand 1 lands in stores, it’ll be very different to the book you’ve already read. We’re not just talking spell checks and maintenance. We’re building characters, settings, and plotlines from scratch. The bones will be the same. The flesh will be almost unrecognisable. And as a thank you to you for supporting me through the years, Parvus will send a free e-book of the revamped Century of Sand 1 to everyone currently (as of 7 Nov 2017) on my mailing list, once it’s complete.

You’ve read the theatrical release. Now you, my long-time fans, get the Director’s Cut delivered to your door.

I’ll wrap up by extending a huge thank you to Colin, Kaelyn and John at Parvus Press for taking me on as their latest author. I’m incredibly excited to start work.

Together, we’re going to make this story amazing. I can’t wait to show you the results.

Want to keep in touch? Follow me on Facebook or check out the Parvus Press FB page if you want to keep up with publishing dates!

The question a lot of horror authors get is, “Why do you have to write such terrible things?” And my answer is usually, “Um, ah, well, it’s entertaining?”

But that’s not really why. I’ve been thinking about what drives me to write horror, and what inspired my series Rust. I could cite a lot of books and shows that I’ve loved (Uzumaki, Twin Peaks, The Ruins) but my love of horror goes all the way back to childhood.

And where’d that begin? The lazy answer would be, “My Dad let me watch Alien when I was six” (true) or “I read Pet Semetary when I was eight” (true) but that doesn’t get to the core of why I write horror. Why I want to scare people. Why I want to scare myself. What truly scares me.

So here are some images from my childhood that’ve never left:

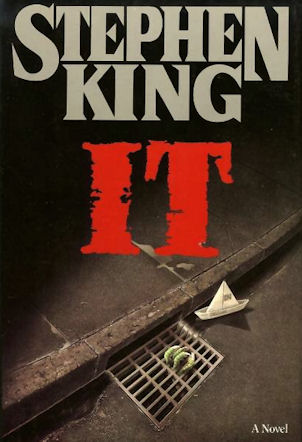

I was on holiday with my parents in Queensland, staying with a family friend. I was maybe six years old. While browsing a bookshelf in a hallway I was startled by the image of a green claw reaching out of a rain-clogged drain. That was the original edition of IT.

On that same holiday, I watched a Saturday morning cartoon where a villain sprayed a city with a chemical that turned everyone into screaming, rooted plants. It kept me awake that night.

On my father’s bookshelf, while browsing for science fiction, I was transfixed by a howling face unwinding on an old cover of Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan.

Finally, in my kid’s edition of Sleeping Beauty, there’s an illustration of the forest of thorns. A man hangs dead, skeletonised. Thorns twine through his eyehole.

The term “body horror” wasn’t in my lexicon when I was six, but those few core images were the beginning of a life-long fascination. I sought it out in books, films, comics. Themes of disfigurement, contortion, manipulation, and transformation were more fascinating and more terrifying than ghosts, werewolves or bug-eyes monsters. It wasn’t about pain – even as an adult that makes me squeamish.

As I write this, I realise it could come across as a “how I became a serial killer” confession. Not at all. I don’t like this stuff. James Patterson doesn’t like kidnapping or murder (I hope). Joe Hill doesn’t hurting children (I hope). These themes scared the shit out of me. They still do. But sometimes you can’t stop worrying at a loose, painful tooth. You understand what scares you better by drilling down to the core.

In all that drilling, I had an awful realization. The people in these shows/comics/books were fiction, but they had a basis in fact. They could be me. That you could escape a mummy/werewolf/Freddie Krueger, but you couldn’t escape a contagion, or a forest of thorns growing instantly around you, or a dimensional portal unzipping your body.

The helplessness that came with that realisation shook something loose in me. Monsters were known. The unknown, on the other hand, and the inevitable, the idea that you could see some sorts of horror coming and be unable to run, to hide, because it’s all-encompassing…

That freaks me out.

So when I set out to write Rust, those old themes boiled up. The manipulation of memories & bodies. The rain that reaches from horizon to horizon. Creatures laying eggs inside you. The blister-sickness. The things in the Pentacost Convent. Peter & Kimberly’s terrible evolution. Worms in eyes. Inevitability.

In many ways, I’m writing Rust so I can terrify child-me all over again. It might be the most honest series I’ve ever attempted. It’s a direct line into all the things that make me want to pull the covers over my head at night. And maybe it’s also a way to exorcise those fears. If they’re on the page, they can’t keep me awake. If I pass them on to you, I’m left free.

Maybe that’s why so many readers are enjoying Rust. To all who’ve already given it a shot, thank you. I hope you’re losing sleep like boy-Ruz lost sleep.

…and yes, I’m working on Rust 4 right now. Will it be done this year? Who knows. But it’ll be creepy as hell when it arrives.

“Madam Director? We have a problem.”

“When?”

“Beethoven. A research squad was sent to observe his composition processes, but he wasn’t there.”

“What period?”

“1802 onward. He’s simply-”

“Calm down, Ms Hart. I’ve seen this before. Who do we have on staff who can play piano?”

“Well, there’s old Norris Friar. Works in time-stream stabilisation. He’s quite good, actually. I heard him play at the office Christmas party. And he knows a bit of German.”

“Does he have field experience?”

“Let me… oh. His records with the department are sealed. Sanitised temporal missions, most likely.”

“Perfect. Here’s what we’re going to do. Fill out form D-37 and schedule Friar for emergency facial surgery. Then run forms BB-2 and BB-5 to head office, have them signed in triplicate, and organise a cache of all of Beethoven’s sheet music, as well as period-appropriate currency. Friar will need, oh, say, eight hundred marks. If we don’t have enough in the store-room, send a team back to retrieve some direct from the bank of Hamburg. And an acting coach! He’ll need to pretend to be deaf.”

“You’re making Friar into Beethoven?”

“Classic bootstrap, Hart. Never fails.”

#

“Madam Director?”

“What now, Hart?”

“It’s Mozart.”

“Vanished?”

“We don’t know when it happened, but there’s simply no trace.”

“Do we have anyone else who can play piano?”

“Friar was our best. He’ll be back on Tuesday’s timestream, but he’s lived in the 1800s for twenty years. Much too old to play the part.”

“This is a problem. Do you know when Friar learned to play?”

“He said once he’d been practicing since childhood, but-”

“Listen, Hart. This is important. We have to go back and interact with an existing agent’s timeline, which means forms P-22, P-23 and XX-Lambda. All in triplicate. We need to locate Friar at an appropriate age… thirteen should do, accounting for slippage. And we’ll need to teach him period-German.”

“You’re taking a child and-”

“This is how bootstraps work, Hart. We only need him to play Mozart for ten, twelve years, and then he can come back as a young adult with a fat pension.”

“But weren’t Mozart and Beethoven contemporaries?”

“Shit. Fill out a form for emergency intersection and shoot an agent back five weeks to tell me to tell Friar not to speak to Mozart when he’s playing Beethoven.”

“The higher-ups won’t like this-”

“Hart, I’ve received more than enough communications from our department ten years down-stream to know that everything I do now only leads to more promotions. Our choices have been sanctioned by the future. Get it done.”

#

“Madam Director, I’m so sorry, but-”

“Who is it this time?”

“Haydn.”

“Jog my memory. Was he important?”

“He’s not remembered as well as Mozart or Beethoven, but he was instrumental in the creation of chamber music.”

“So we can’t just let him-”

“Also, he taught Beethoven.”

“This is getting complicated.”

“That’s what I said last week, Madam Director.”

“Quiet, Hart. Let me think. Haydn was twenty years older than Mozart. That means we can retrieve Friar as soon as he returns from his period as Mozart, put him under the knife-”

“That’s another D-37?”

“So long as he and the later Friar look different enough, he can be Beethoven’s teacher without ever knowing.”

“Forcing an agent to teach himself, in the field…”

“Well, now we know why his records were sealed. Make sure that, when Friar returns from playing Haydn, we dump him at least twenty-four months ago. Get him a job with time-stream stabilisation. Far enough back so I won’t know I did it.”

“We’re risking some major tangles, Madam Director-”

“Just get it done, Ms Hart.”

#

“Hart?”

“Yes, Madam Director?”

“Are all the great composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth century where they should be?”

“As far as I know.”

“Have we located the bodies of the original Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven yet?”

“Teams are still searching-”

“If they’d ever found them, they’d have reported by now. I don’t like not having control over the situation.”

“What are you suggesting?”

“Something drastic. Get me three copies of form G-22.”

“You can’t be-”

“It has to be done. For consistency, for history, for the stability of the universe. Now, we’ll need a field agent with language skills, a talent for blending in…”

“Friar just got back from being Beethoven.”

“Do you think he can effectively dispose of a body?”

“He’s spent almost fifty years of his life play-acting in the reign of the Habsburgs. I think he’d relish the chance to kill his way across Germany.”

“I trust your judgement, Hart. Schedule three jumps – one to remove the original Mozart, one for Haydn, one for Beethoven. Oh, and Hart-”

“Yes?”

“They can never be found.”

#

Friar was back, now almost seventy years old and sick to death of the Germans. He’d thrilled the Salzburg courts as Mozart, given birth to the modern symphony as Haydn, taught Beethoven before returning to become Beethoven, and then skipped back along his own timeline to vanish the originals. Three musical legacies secured. No major anomalies. Time had not imploded.

The director leaned back in her chair, content for the first time in months, and felt a ring of cold steel press against the nape of her neck.

She knew. “Ms Hart?”

“Madam Director. I’m sorry.”

“This is impossible. I’ve received reports from the future. I’m the director for another ten years-”

“Twelve, actually. But things got too tangled. Orders came from twenty years down-stream. You have to go.”

“Whose orders?”

“Officially, or unofficially?”

“Officially.”

“Your orders. You sent the command back. Form C-3, and a D-37. The C-3 is your kill-order, and the D-37…”

She nodded. “You take my face. Very neat. Which makes you the future director. Which means you authorised your own promotion.”

“Classic bootstrap.”

“You learned from the best, Hart. But what if I filled out my own C-3 and sent Friar back to stop you?”

Hart paused. A quaver of uncertainty crept into her voice. “You didn’t.”

“No.” The director closed her eyes and smiled. “Not yet.”

– – –

Enjoyed this short? Check out my other work on Kindle, such as my short story collection Future Tides, my fantasy series Century of Sand, or my horror serial Rust!

I don’t get choked up over celebrity deaths. I mean, they’re interesting people very far away, I’m just a fan of their work, we never shook hands…

But Sir Terry Pratchett passed this morning, and I feel I’ve been shaking hands with him my entire adult life, ever since a good friend gave me a hardcover edition of Hogfather for my eleventh birthday. I didn’t understand half of it, but I knew I’d been introduced to something elemental. A story that my parents didn’t mind me reading that was also deeply adult, unsettling, possibly dangerous.

Of course, I backtracked to his first novel and started reading forwards. I wasn’t even a teen and escapism was a survival tactic. Were there other authors I enjoyed at the time? Sure – Card, King, Brooks. All of them inspired me in some way to imagine further, to create stories in my head, but it was Pratchett who built in me the fanaticism required to put pen to paper, to understand that this was something I could do, that I had to do.

My first real attempts at writing were all Pratchett imitations. They were terrible but necessary. I saw, in his works, how he’d grown as an author, how his prose had tightened and matured between The Colour of Magic and Sourcery. I knew I could do the same.

I read Pratchett religiously until I was perhaps nineteen, when I decided I’d outgrown him. I put my books aside, in a box, for many years. It was my fiancee, also a great fan of Pratchett (probably a bigger fan than I) who encouraged me to pick them up again, and I discovered a whole new level of allegory tucked neatly inside the fantasy/satire wrapper I’d enjoyed throughout my childhood. I found myself knee-deep in Wyrd Sisters, laughing out loud in an airport lounge, remembering just how dangerous Discworld truly was for an eleven year old.

Because Discworld, and Sir Terry, was and will always be a scalpel. Fantasy? Yes. Satire? Sure, but something deeper than that. A surgical blade drawn across meat. It had the power to leave me laughing even as a knot of unease grew in the pit of my stomach, the slow understanding that this is not how things should be.

Sir Terry showed me injustice and class politics and systematic oppression. He took what I knew as a kid… and later, as an adult… and upended it. And he did it with a smile.

No other author ever did that for me. No other author ever felt so much like a friend.

Sir Terry is gone. I guess we should be glad we shared his company for so long, given his diagnosis eight years ago. And yet…

I don’t get choked up over celebrity deaths. Except this once. Today, I’m mourning.

There are characters in Pratchett’s work I grew so close to that they felt like friends – Carrot, Angua, Susan Sto-Helit, Vimes, and of course, Death. But they’ll always be close enough to touch. Sir Terry, though… there could only ever be one. The world couldn’t deal with two minds like that at once.

Vale, Sir Terry Pratchett. You’ll always be on my bookshelf. Is it too sappy to say you’ll always be in my heart? Probably. I said it anyway. Sir Terry taught me to speak the truth.

– – –

“I meant,” said Ipslore bitterly, “what is there in this world that makes living worthwhile?”

Death thought about it.

CATS, he said finally. CATS ARE NICE.