I read a lot, and I enjoy most of what I read, but sometimes a book hits me somewhere deep and sets up root in my gut. It’s getting rarer – I read most of the books listed here when I was a child, and at that impressionable age when fiction seems far more real than reality.

These aren’t just books that I love. These are books that have embedded themselves so far into my brain that I spend my waking moments trying to figure out why they work, how they work, and how I can do better. I want to recreate all these worlds, or at least the giddy excitement of those worlds, through my own novels. I want to keep those ideas alive forever.

In no particular order:

Neuromancer, by William Gibson

Maybe it’s the obvious #1, but Neuromancer will always be dear to my heart. Even re-reading it today, when so many of the ideas seem quaint (inserting gig-sticks of data into slots behind your ear? Adorable!) Neuromancer is still a breathless, non-stop story where every page reveals a new and dangerous concept. Often imitated, never equalled.

Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson

Snow Crash did everything Neuromancer did, but with a wry, knowing smile. Once again, every page was packed with brilliant ideas, but always with tongue firmly planted in cheek – and for that, it was somehow more believable. It was less about tech and more about the cultures that result from that tech, and I’ve always wished I could recreate that authenticity in my own work.

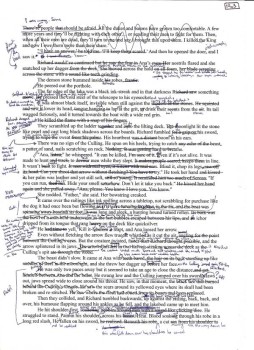

IT, by Stephen King

I saw it for the first time when I was eight years old, on a friend-of-my-parents bookshelf. The cover – a rotten, clawing hand reaching up from a storm-drain – fascinated and terrified me. I didn’t get my hands on a copy for another four years, eventually borrowing it from the school library and hiding it under my bed. It gave me nightmares for weeks. It taught me that horror isn’t about blood and guts – it’s about isolation, and the things you can’t quite see, and the feeling of your friends turning their back. It showed me that horror isn’t just a genre, but a necessary aspect of the human psyche. Since reading IT, I’ve tried to incorporate aspects of horror into all my work, sometimes succeeding and sometimes failing miserably.

The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkein

It wasn’t the elves that won me over, or the songs, or the epic battles. It was the sense of distance and scale, and the realisation that you can’t just go on an adventure in your lunch break – the Fellowship wasn’t home in time for tea. They lost their lives to that journey. Discovering Middle Earth was beautiful and tragic at the same time, because I could see the destruction left behind wherever the Fellowship travelled. Also, Shelob scared the hell out of me.

Ubik, by Philip K Dick

I had no idea what was going on until the final page, and then I had even less of an idea, but I still loved it. Ubik took dreamscapes and made them tangible and dangerous. How Dick pulled it off, I have no idea.

The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco

A terrifying murder mystery set in an abbey, lashed through with biblical mythology and suspicion and more villains than heroes? I don’t know whether this book is more historical fantasy or detective noir, but it was an exercise in terror and tension from beginning to end, and a beautiful lesson in both plotting and the art of the red herring.

The Road, by Cormac McCarthy

I wrote like Cormac McCarthy for about a year straight after finishing this book, and it was a long time before I trusted in quotation marks. I’m still striving to emulate his starkness of prose and elegance of action.

The Stars my Destination, by Alfred Bester

Best anti-hero in literary history, period. The first novel that (for me, at least) combined space-opera concepts with a story driven entirely by one small, almost insignificant character. Exposition blended seamlessly with a balls-to-the-wall tale of revenge. From the moment I read this book, I knew I had to hurt my characters at every turn.

Feverdream, by Ray Bradbury

A short story about a teenager getting infected with a mystery space-virus that slowly takes over his body and mind? Pure nightmare fuel for little-boy-Ruz, but an incredible introduction to the concept of body-horror. My short story What You Bring Back, and much of Century of Sand, took their cues from this terrifying piece.

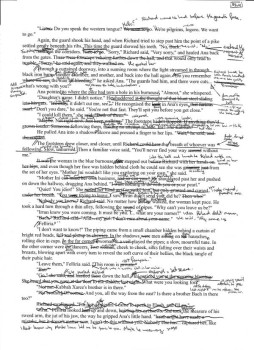

Gorky Park, by Martin Cruz Smith

Finally, a novel about fingerless Russian women turning up in the snow. I don’t know why this book worked so well on me. Perhaps because the central mystery was, at its heart, about people with strange motivations more than any grand plot or twist. The world wasn’t changed by the investigation. No assassination was prevented. Just a small measure of justice in a troubled country. It wasn’t grand, but it was human, and all the more powerful for it.

Fill me in, guys! What books have sunk their claws into your brain? When you sit down to write, who are you wishing you could be? What scene are you wishing you could recreate?